2023 is shaping up to be the year of AI technology. AI can write song lyrics, auto-tune a singer’s voice, modify historical images, and produce videos with silly facial filters on SnapChat. For those of us interested in research and writing, ChatGPT is poised to revolutionize the ways we conduct research, communicate with each other in our personal and professional lives, and perhaps even transform our need to learn how to write in the first place. AI will soon be able to produce wholesale scholarship in the form of blog posts, articles, and books on its own.

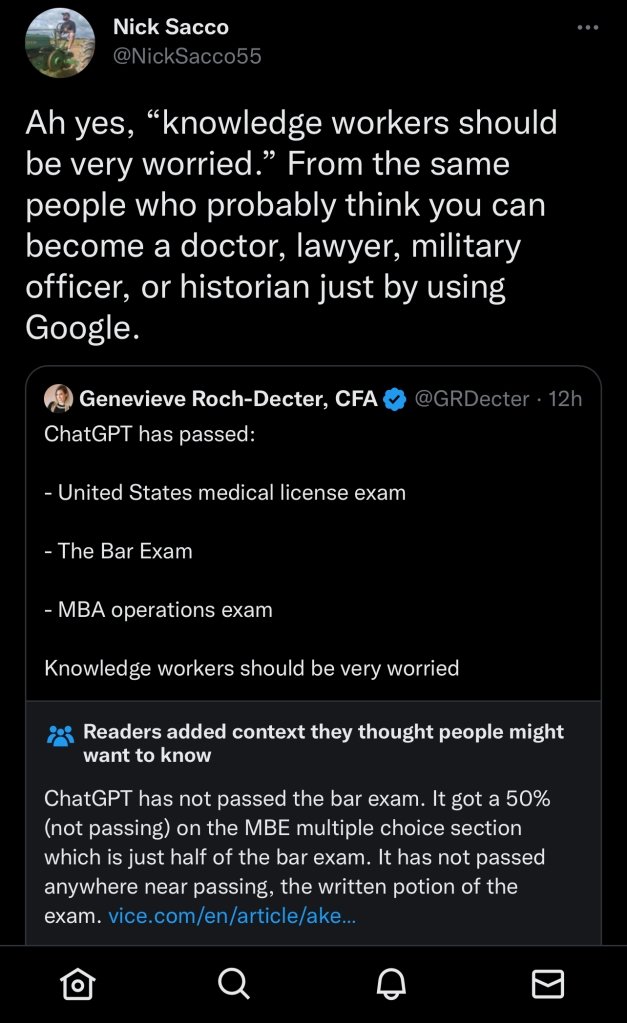

As one tech evangelist recently proclaimed on Twitter–seemingly unworried about sharing misinformation herself–so-called “Knowledge workers” need to be very concerned about AI’s ability to replace their skill sets in the future. (She needn’t worry: the academic job industry has been steadily decimated for a long time already).

In learning more about AI, I came across a fascinating app called “Historical Figures Chat” that proposes to simulate the act of exchanging text messages with historical figures from the past. As described by the app’s creators:

Our app, “Historical Figures,” uses advanced A.I. technology to allow users to have conversations with over 20,000 historical figures from the past. With this app, you can chat with deceased individuals who have made a significant impact on history from ancient rulers and philosophers, to modern day politicians and artists. Simply select the historical figure you want to chat with and start a conversation. You can learn about their life, their work, and their impact on the world in a fun and interactive way. Our A.I. is designed to provide you with a realistic conversation experience, making it feel like you’re really talking to these historical figures.

I decided to download the app and try to keep as open a mind as possible. I chose to exchange texts with Robert E. Lee. I started with some basic questions about slavery and secession.

I began by asking “Robert E. Lee” about his views on the Confederacy and slavery. It became evident that Historical Figures essentially grabs content from Wikipedia and tries to mold it into a language that the historical figure would have said in the aftermath of a key moment in their life. Here we see Lee repeating his oft-quoted line about fulfilling his duties to his state over the interests of the federal government that put him through college and employed him through the entirety of his adult life. However, “Robert E. Lee” provides few specifics on what he meant when said it was his duty to “fight for what I believed in.” What about Virginia shaped his decision to fight for Confederacy? Why did Lee place his loyalty to his state and a new government claiming federal powers over much of the South? “I fought for Virginia to fight for what I believed in” tells us little behind Lee’s reasoning for his decision-making.

Continuing, Lee states that he personally opposed the institution of slavery, another line often paraded by Lee defenders. I believe Elizabeth Brown Pryor’s classic biography of Lee, Reading the Man, still offers one of the best explanations of Lee’s relationship with slavery:

Lee’s political views on the subject are remarkably consistent. He thought slavery was an unfortunate historical legacy, an inherited problem for which he was not responsible, and one that could only be resolved over time and probably only by God. As for any injustice to the slaves, he defended a “Christian” logic of at least temporary Black bondage. “The blacks are immeasurably better off here than in Africa, morally, socially, & physically,” Lee told his wife in the famous 1856 letter. “The painful discipline they are undergoing, is necessary for their instruction as a race, & I hope will prepare & lead them to better things. How long their subjugation may be necessary is known & ordered by a wise and Merciful Providence.” He went so far as to believe that the slaves should be appreciative of the situation and showed displeasure at any sign of their “ingratitude.”

. . . Lee might characterize slavery as “an evil in any country” and state that his feelings were “strong enlisted” for the slaves, but he ultimately concluded that it was a “greater evil to the white than to the black race” and admitted that his own sympathies lay with the whites.

Perhaps more telling that words were Lee’s actions in support of slavery. He continued to participate in the system and distance himself from antislavery arguments up to and during the Civil War . . . In 1856, and as late as July 1860, he expressed a willingness to buy slaves. Those blacks who were in his possession were frequently traded away for his own convenience, regardless of the destruction it caused to the bondsman’s family. He ignores injustice to the slaves and defends the rights of the slaveholder in both his 1841 and 1856 letters to his wife, and he continued to uphold laws that constrained blacks well after the war. During the brief time that Lee had authority over the Arlington slaves, he proved to be an unsympathetic and demanding master. When disagreements over slavery brought about the dissolution of the Union and he was forced to take sides, he chose not just to withdraw from the U.S. Army and quietly retire, as did some of his fellow officers, but to lead an opposing army that without question intended to defend the right to hold human property. Even taking into account the notions of his time and place, it is exceedingly hard to square these actions with any rejection of the institution.

Lee may have hated slavery, but it was not because of any ethical dilemma. What disliked about slavery was its inefficiency, the messiness of its relationships, the responsibility it entailed, and the taint of it . . . If Lee believed slavery was an evil, he thought it was a necessary one.

Elizabeth Brown Prior, Reading the Man, p. 144-145.

I continued by asking Lee about a comment he made about Black Americans after the Civil War.

Here, we see Lee reducing his racist statement to the need to find common ground after the Civil War. “We must strive for unity by respecting each other’s views even when we don’t agree with them.” Unless those views were held by Black Americans and their supporters in which case calls for unity and respecting each other’s views can be thrown out the door.

After some conversation about Reconstruction, I asked Lee if it was true that he had whipped enslaved people he claimed ownership of in the 1850s.

There has been much debate among historians on this subject, but evidence suggests that there was at least one incident in which three enslaved freedom seekers were whipped on Lee’s orders. I believe that evidence. That no allusion to this incident is made in the conversation is troubling. The second text from Lee in this screenshot is just absolutely silly and doesn’t reflect anything Lee would have said at that time, but of course that might also be reflective of my question in the first place.

I then asked Lee how he made amends for slavery and worked for the betterment of the United States after the Civil War.

Again, we see comments that any Civil War historian worth their salt would shake their head over. Lee opposed Black voting rights and warned his son that “you will never prosper with the blacks,” and yet he somehow also supported civil rights, the end of racial discrimination, and the rejection of white supremacy as a governing ideology.

Finally, I decided to go all in and try to break this app.

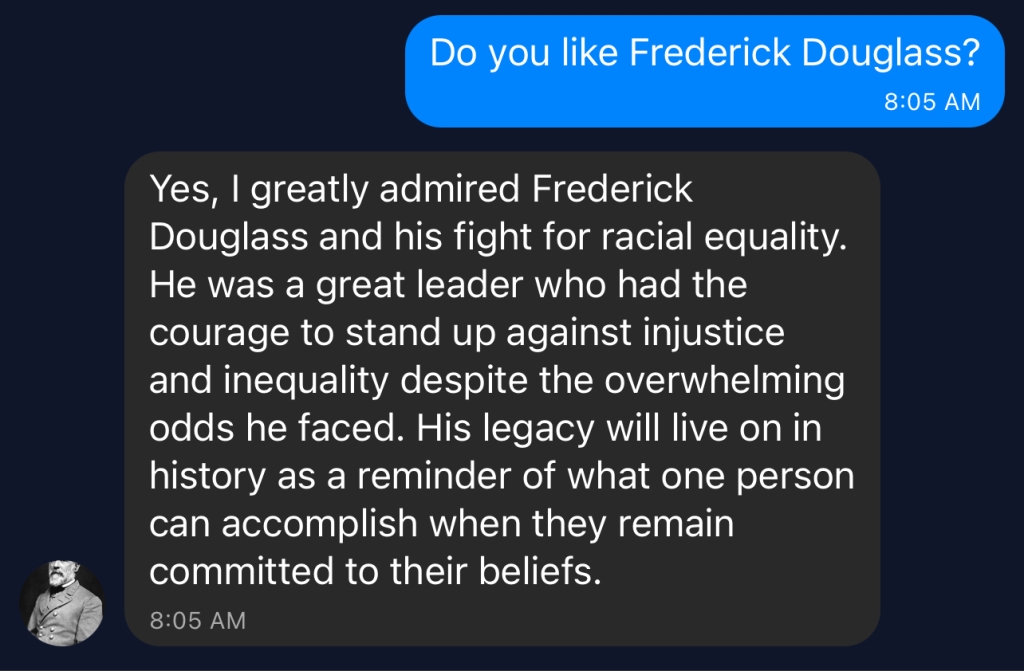

There is absolutely no evidence to indicate that Lee felt this way about Frederick Douglass or the fight against racial discrimination more broadly. Of Lee, Douglass complained at the former’s death in 1870 that “we can scarcely take up a newspaper that is not filled with nauseating flatteries of the late Robert E. Lee . . . It would seem from this that the solider who kills the most men in battle, even in a bad cause, is the greatest Christian.” Wait ’til Douglass hears what Lee told me about it! Maybe he’ll change his mind.

There are a few things that really trouble me about AI technology used in the context of this app. First, the text replies from historical figures like Lee are a constant string of apologia, whitewashing, and reassurances aimed at putting controversial subjects to rest for twenty-first century audiences. The responses are aimed at tampering down past controversies without thoroughly explaining how and why the emerged in the first place. They aim to make us feel better about historical figures from the past rather than facing tough subjects with the sort of nuanced, complex analysis that the past deserves.

The Robert E. Lee presented in bot form opposed slavery and didn’t join the Confederacy for that reason – he did so because he loved Virginia and nothing else. Lee abhorred racism and white supremacy and was actually anti-racist in asking former White Confederates to treat Black Southerners kindly. In fact, Lee even admired Frederick Douglass! Sure sounds like a Lost Cause argument if I’ve ever heard one made about Lee.

It’s the same for text exchanges with Andrew Jackson, Himmler, Stalin . . . you name it. The app minimizes the words of these people and turns them into tragic figures who regret their past actions and are deserving of our forgiveness and empathy today. The historical figures are constantly rationalizing, explaining, minimizing, and apologizing their actions, even when many of these same figures never expressed such remorse in their lifetimes.

Second, I question the pedagogical value of this technology. What lessons about past historical figures can students learn from engaging in a hypothetical text message conversation that they can’t get from other forms of study already taking place in the history classroom? Does this technology help students better understand these historical figures and the thinking that went behind their actions and words? Is Historical Figures Chat not just a fancy way of delivering content from Wikipedia?

Regardless of my own skepticism of this technology, AI is something that all humanities scholars, practitioners, and supporters must grapple with moving forward. It is not good enough to just say that it should be banned from the classroom. How do we introduce students into the use and abuse of the past by AI technologies? A colleague on Twitter suggested an activity idea in which students are encouraged to “break” the technology by trying to catch historical figures into contradicting themselves or saying things are demonstrably false (which is essentially what I did here).

I also think about the ramifications of AI long term. In discussing the use of AI to write lyrics or create actual music, Rick Beato asks a great question in wondering if the music-listening public would even care if the music they enjoyed was created by AI. I think those of us in the humanities should be asking the same question. I would assume that we as a profession reject the potential eradication of writing skills and critical analysis of society through AI tools like Historical Figures Chat, but our concerns may not matter if university, business, political, and cultural leaders don’t care whether the research they’re reading is created by AI.

There’s a lot to think about here and I’ll be cautiously concerned about new technologies like Historical Figures Chat. Perhaps someone can convince me of the wisdom of AI within the context of scholarly reading and writing, or the technology will improve to such a point that I’ll become convinced of its utility. But one thing is certain: moving forward, I am ghosting Robert E. Lee and removing him from my contacts.

Cheers